We live in an age infatuated with the smooth – surfaces without resistance, systems without friction, stories without surprise – an effect of what critics now call “literalism“. Korean-German philosopher Byung-Chul Han calls smoothness the aesthetic of our time: glossy interfaces, seamless shopping, frayed edges airbrushed out. Smoothness soothes, sure, but it also flattens! When everything glides, nothing grips. We stop noticing, touching, lingering. We consume, and move on.

I want to argue for the opposite tendency: rewilding in design and culture, and a parallel rise of the artisan economy and a new luxury that measures value not by polish but by aliveness; patina, irregularity, provenance, and time. This is also an argument for what I have elsewhere called anti-trends: long-horizon patterns that outlast fashion and support genuinely nourishing lives.

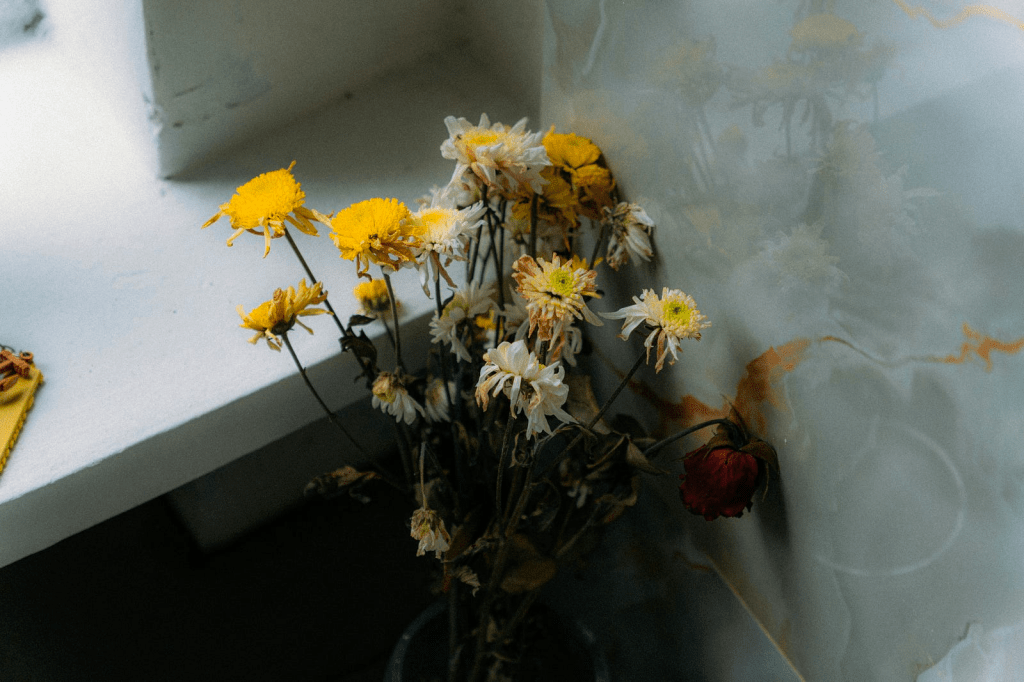

My first encounter with rewilding was through George Monbiot’s book Feral. What really struck me, when I read the book was that rewilding, to him, means creating the best possible conditions and then stepping back so complex ecologies can unfold. The human role is catalytic, not controlling. Translate that into product design and you get a radical shift: design the frame, plant the seed, then let the object live. A rewilded object isn’t sealed into a final, pristine state; it is slightly open, ready to be co-authored by use, wear, repair, stories and memories. Over time it acquires surface stories – scuffs, sun, oil from hands, small fixes. The object becomes more itself in the user’s care.

This approach obviously demands courage from designers: the courage to release something not “finished” in the showroom sense; the courage to allow diversity of outcomes, even idiosyncrasy. Monbiot describes in his book how reintroducing wolves to a national park can reshape a valley. Good design works the same way: introduce the right “predator,” then allow use, wear, and care to do the ecological work.

Anti-trends are not counter-trends. They are the slow currents beneath the surface, the rhythms of human living that keep returning—care, repair, belonging, seasonal cycles, ritual. An anti-trendy life is not ascetic, but it is authentic, shaped by meaning rather than market tempo.

Even if we removed the pressure of fashion trends, perceived obsolescence would still exist, because some objects fail to feed us aesthetically over time. They are trivial, inflexible, or age poorly; their beauty is brittle. Conversely, certain things gain aesthetic power with use. Think of truly vintage pieces – garments, furniture, bicycles – that have become more beautiful through wear, as if someone’s love has sunk into the surface. We can design this kind of aesthetic resilience from the start by thinking beyond attraction-at-purchase toward long enjoyment, choosing materials that take patina well, making construction honest so repair is invited rather than hidden, and building for maintenance, modularity, and graceful aging. The task is to plan for an extended user phase, not simply a powerful launch.

Balance matters. In Everyday Aesthetics, Japanese-American philosopher Yuriko Saito writes about “the familiar strange,” which is the small, concealed delights in ordinary objects; e.g. a hidden lining that greets you when you open a bag, a chair that looks heavy but surprises the hand, a subtle texture that rewards touch. These moments puncture monotony without turning the everyday into spectacle. But if we demand spectacle everywhere, we sacrifice everydayness itself.

The ordinary can and should be quietly satisfying. I often describe this as two complementary pleasures: the pleasure of the expected; rhythms that hold us, repeatable, reliable, calming, and the pleasure of the unexpected; the little punctum (in the Roland Barthes sense of the word) that pricks our attention and widens us. Good design understands both. Not everything must astonish; very little in life could sustain that pitch. Most of living is routine: cooking, working, moving, resting. Most objects should support and enrich those rhythms – through tactility, flexibility, inclusivity – so we don’t need endless novelty to stay awake to our days.

Han’s critique of the smooth helps explain why we feel starved in a world of perfect finishes. When you sand away every edge, you remove resistance – and with it, character.

The smooth is camera-ready, but it doesn’t hold us. We touch, but we don’t attach. Gratefully though, a different luxury is emerging, braided with the artisan economy: materials with memory that deepen rather than degrade; visible construction – stitches, joints, rivets – that dignifies repair; local provenance and craft lineages, where techniques, weaves, dyes, and patterns are documented and carried forward, and open endings in which parts can be swapped, finishes can evolve, and the owner’s care becomes part of the final form. This luxury is not louder, it is richer. Its currency is time, care, and story.

Rewilding doesn’t stop at the object. It’s also a way of organising how we make and use. Open design and open processes instead of locked-down perfection. New consumption habits: keeping, mending, sharing, taking pride in long use. Circular pathways that move things back through the system – service, take-back, re-manufacture – so stories continue instead of being cut short. Cultural stewardship that credits artisans and records techniques without freezing them in amber. This is where the artisan economy lives. Not as nostalgia, but as a living system moving at the pace of people and place.

Ultimately, anti-trends are about belonging – to a place, to a community, to time itself. They orient us toward rhythms we can keep and that we can keep cherishing. Rewilding is an ethic as much as an aesthetic: making room for life to show up, in objects and in us. The smooth will keep seducing us with ease, speed, and shine. But if we want objects – and lives – that last and that we can justify, we need friction, grain, and growth. We need things that can withstand and deepen. New luxury isn’t a brighter gloss; it’s a slower glow. It is the courage to release the finished-but-unfinished, to let use write the final lines, to choose an economy that values making, maintaining, and meaning over perpetual replacement.

Leave a little roughness, and beauty will have something to hold on to.